A deep dive into how a bizarre rumor derailed one of the world’s biggest companies and what it teaches us about brand vulnerability.

Introduction

In the 1980s, the United States was gripped by the Satanic Panic, a cultural hysteria that blurred the line between concern and paranoia. Books, talk shows, and televised sermons warned of hidden symbols, secret cults, and a rising tide of Satanic influence in everyday life. Among the many targets of this moral panic was a company few would expect: Procter & Gamble.

At the time, P&G was a household name with a sterling reputation. Yet an urban legend, fueled by misinformation and religious fervor, chipped away at the company’s image and forced it into damage control. This is the story of how a multinational corporation became entangled in conspiracy theories, and what that cautionary tale still means for brands navigating today’s misinformation landscape.

The Rumor That Wouldn’t Die

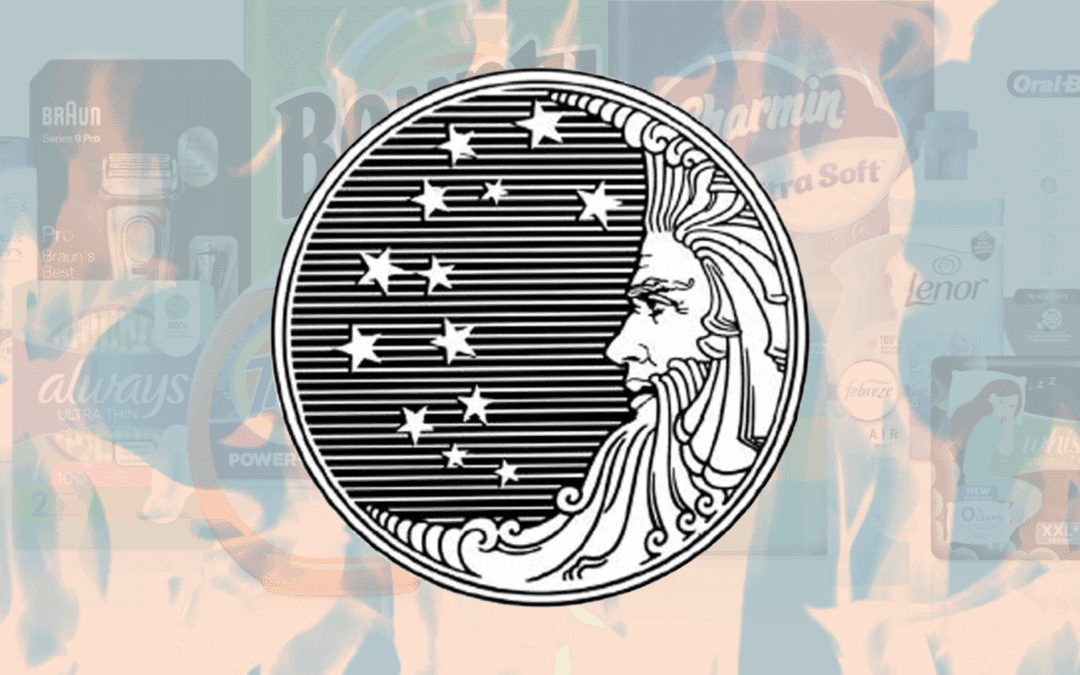

At the center of the controversy was Procter & Gamble’s logo: a bearded man in the moon gazing over a field of 13 stars. Originally designed in the 1800s, the image symbolized the original American colonies and the company’s long-standing roots. But in the 1980s, rumors began to spread. Some claimed the man’s beard contained hidden 666 numerals and devil horns. Others said the owner of the company went on The Phil Donahue Show and admitted to donating to the Church of Satan.

It wasn’t just fringe conspiracists fanning the flames. The rumor was printed in religious pamphlets, shared from church pulpits, and promoted by televangelists with massive followings. Some multi-level marketing distributors—most notably from Amway—amplified the story, urging customers to abandon P&G in favor of “Christian” alternatives.

The details shifted, but the message remained: P&G was, supposedly, in league with the Devil.

The Real-World Fallout

Despite being completely false (that Phil Donahue episode never existed), the rumor did real damage. For years, P&G faced boycotts, denunciations from prominent religious leaders, and a growing wave of public distrust. The backlash reached a peak in the late 1990s when the company sued a group of Amway distributors for knowingly spreading the falsehoods. In 2007, they were awarded $19 million in damages, sending a clear message about the consequences of defamation.

Still, the damage was done. For many, the association stuck. P&G eventually removed the moon-and-stars logo from most products, opting for a cleaner, more modern identity. The company released public statements and education campaigns to clarify the truth, but it took years to rebuild trust that had eroded almost overnight.

Why This Conspiracy Stuck

The P&G saga wasn’t a one-off. It arose from a perfect storm of visual, cultural, and psychological conditions that made it a conspiracy theory tailor-made for the 1980s.

Visually, the logo invited misinterpretation. The ornate, hand-drawn image could easily be twisted into whatever a suspicious viewer wanted to see. Culturally, the U.S. was in the grip of widespread fear around Satanic ritual abuse—fueled by high-profile court cases, sensational talk shows, and a general sense that evil was lurking just beneath the surface of everyday life.

Then came the delivery system: chain letters, cassette tapes, and flyers left on church windshields. Long before the internet, this analog virality gave legs to rumors that would otherwise have fizzled out.

Brand Vulnerability in the Age of Misinformation

This might sound like ancient history, but it’s not. In recent years, brands like Wayfair and Balenciaga have come under fire from conspiracy theorists, accused of everything from child trafficking to occult rituals—all based on misinterpreted visuals or speculative links.

The P&G case shows that no brand, no matter how well-established, is immune. Misinformation now spreads even faster thanks to algorithms that amplify outrage and user-generated content. But the core ingredients remain the same: ambiguous visuals, cherry-picked “evidence,” and a culture ready to see signs where none exist.

That’s why today, brand design is about more than aesthetics. It’s about clarity, intention, and cultural awareness. Symbols carry meaning, especially in a climate primed to uncover hidden ones. Whether you’re creating a logo or scripting a video, understanding the broader cultural temperature is critical.

What P&G Did Right—Eventually

To their credit, Procter & Gamble didn’t look the other way. Their legal action helped set a precedent for how companies can respond to false advertising and defamation. Their PR team communicated clearly and consistently. And in time, the brand updated its visuals while maintaining its reputation for quality.

Conclusion

The story of P&G during the Satanic Panic is a powerful reminder that even the most bizarre rumors can take root and cause real harm. As modern brands play with irony, occult aesthetics, and viral marketing today, the stakes remain high. Not every symbol is just a symbol. Not every joke lands the way it was intended.

When conspiracy meets commerce, the result can be anything from viral gold to a PR nightmare. That’s why our branding process begins with research—not just into the competition, but into the culture. Symbols carry history, and we believe design should never happen in a vacuum. By understanding what imagery evokes, implies, or inflames, we help brands communicate clearly and protect their reputations in the process.

Recent Comments